In James F. Lawrence's "Testimony to the Invisible: Essays on Swedenborg," Czeslaw Milosz' essay, "Dostoevsky and Swedenborg," points out that when Leonid Grossman published the catalogue of Dostoevsky's library in 1922, no fewer than three books by

A.N. Aksakov (1817-1860) on Swedenborg's religious experiences were listed. Swedenborg (1688-1772) was a Swedish industrialist who experienced a sudden conversion at the age of fifty-six. He claimed to have visited Heaven and Hell, and to converse with angels. His religious writing was influential across a wide array of writers: Emerson, Baudelaire, Blake (whose "The Marriage of Heaven and Hell" was modeled on Swedenborg's account), Goethe, Jung, Poe, Yeats - a diverse list including, of course, Dostoevsky. Russian artists and painters were also influenced by Swedenborg's etherial views of nature and the cosmos. Father Zosima's dying words, as "transcribed" by Alyosha, reveal some acquaintance with Swedenborgian cosmology. Dear Superaddressee, Natasha does not pretend to know a great deal about Swedenborg, indeed, it is difficult to find anyone who does. With a sinking heart, one reads Milosz' descriptions of Swedenborgian beliefs, and throws up one's hands, and is forced to launch out on one's own, unsupported by such scholarship! Swedenborg believed in the "correspondances" between worlds, the world of angels and spirits, and the present world. Dostoevsky was interested in spiritualism, as well, but was, like William James, unable to make the final commitment (Frank, "Mantle" 214). Swedenborg's system is more or less laid out in this passage, from "Talks and Homilies" of Zosima: "Much on earth is concealed from us, but in place of it we have been granted a secret, mysterious sense of our living bond with the other world, and the roots of our thoughts and feelings are not here, but in other worlds. . . . God took seeds from other worlds and sowed them on this earth, and raised up his garden; and everything that could sprout sprouted, but it lives and grows only through its sense of being in touch with other mysterious worlds; if this sense is weakened or destroyed in you, that which has grown up in you dies. Then you become indifferent to life, and even come to hate it. I think so" (320). The concept of the animal world as spirit messenger is also throughout the novel:

Zosima's bee on its way, the dog and its slavish devotion, the meek-eyed horse who submits to whipping, the innocent green leaves turning their silver undersides to the wind, all sacred. This is a Swedenborgian notion. Dostoevsky also borrowed from Swedenborg the use of color symbolism (see

Joel Hunt).

There are other notions of Dostoevsky's, ones that I'd say were Mormon in character, but again, I am no theologian. In Dostoevsky's time, there were a people called "

Russian Mormons, " but their origins indicate they are not likely associated with American Latter-day Saints. Missions representing the American Saints, for their part, arguably did not tackle the great expanse of Russia, although Dostoevsky might well have run into a few in Europe during his gambling days. Waves of missionaries were sent to Europe for recruiting purposes beginning in 1837, however, mainly to the British Isles and Scandanavia. In any event, the

Book of Mormon was not translated into Russian until 1980, but French and German versions were available in 1852, when Dostoevsky was still in Semipalatinsk. One would like to think that if such material came across his path, he would be interested in it, too, as he was very curious, reading the Koran along with Kant. He also had an interest in America - he loved Poe, he cites Fenimore Cooper in the closing pages of "Brothers." However, that is a Mormon trail that's hard to follow. What, then, is Mormon about "The Brothers Karamazov"? In the opening passages to "The Grand Inquisitor," Ivan talks about the days when the Madonna, saints, Christ and God himself were brought to earth in poetry and play, and even quotes

Tyutchev, the poet: "Bent under the burden of the Cross; The King of Heaven in the form of a slave/Walked the length and breadth of you,/blessing you, my native land" (248). Then Ivan's story of Jesus visiting Spain during the Inquisition begins. As anyone knows, the Book of Mormon's biggest message is that Jesus came to America and walked among men after he rose from the dead. This small, revolutionary, proposal is why most Christians call Mormons heretics. Mormon theology also allows for a spiritual progression from man to god. To Christians in the west, this sound heretical. But to an Orthodox believer, perhaps not so. (Click

here for Natasha's theological cheat sheet.)

With relief, I turn to Lee D. Johnson's essay, "

Struggle for Theosis: Smerdyakov as Would-Be Saint" in Jackson's fine anthology of essays. Theosis is "central to Orthodox theology and crucial to the religious thematics of 'The Brothers Karamazov' on the whole. This concept . . . the Orthodox belief that human beings are capable of partaking in the very divinity of God, that such participation is, in fact, the end goal of all Christians. As the fourth-century saint Athanasius summarizes, 'For He was made man that we might be made God.' Originally, the doctrine of theosis, or deification, was sternly distinguished by Eastern church fathers from the seemingly similar but originally pagan concept of apotheosis, whereby a human being does not so much share God's divinity as become god himself. Indeed, the doctrinal battles that gave birth to the Seven Ecumenical Councils (the councils that form the backbone of the Eastern Orthodox Church) were primarily concerned with achieving precise Trinitarian and christological formulas, carefully balanced definitions that would, on the one hand, preserve the possibility of theosis without, on the other, opening the door for any heretical tendancy . . . that resembled the pagan concept of apotheosis. Dostoevsky, well read in patristic literature, incorporates these religious conceptual battles into the thematic structure of his novel . . ." (75). The Eastern Orthodox church's struggle over man's potential for divinity also finds expression in historical and contemporary Mormon thought,

as evidenced by

this article originally published in "Dialogue, A Journal of Mormon Thought."

The 1840s, when Dostoevsky himself was toying most dangerously with utopianism, were the seedbed for

Fourierism, Icarianism, and American utopian communities, such as Robert Owen's, Anna Lee's, and Joseph Smith's. Of the many forms of utopias that sprang up then, only one has survived as a religious force. In his novels and travel writings, Dostoevsky refers to Fourier, and Cabet, related utopian idealists. Cabet, the founder of Icarianism, a French sect, moved his followers to America, indeed, he actually purchased the deserted Mormon mecca, Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1849, and made it his new utopia, after the Mormon Prophet's execution and the Mormon's exodus to Salt Lake City in 1848. Utopian ideas never wholly left Dostoevsky, and not surprisingly, utopians today find in him a rich resource for discussions about theology, theodicy, and apotheosis.

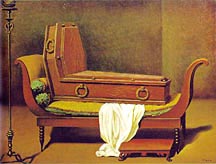

Photo credit: 1) William Blake, "The Marriage of Heaven and Hell" frontispiece, 1790-1793, from kaliope.com. 2) Paul Kline, Montgomery County Mormon Temple at Dusk, from Montgomery County, MD 13th annual photo contest on the county website.