The dirty disorder of the Captain's hovel match his unkempt and provisional life, while Father Zosima's digs are heavenly, a garden, and inside, one finds "crude and poor" furnishings, no more than necessary, but also "porcelain eggs," the special gift of royalty, as well as "expensive prints" of Italian artworks. One imagines Dostoevsky's particular favorite, an insipid Raphael Madonna, here.

Father Ferapont's cell is correspondingly wild and hallucinatory, filled with flickering lights and the darkened images of saints, on the wild edge of a dark forest. Ivan takes refuge in tavern, but not even a private room: he is a man of the commons, always taken in the crossroads. His private space is not revealed until very late in the book; it happens to be a large-ish space, very private, with a gate and a deaf servant, full of rooms that he hardly uses. This is a metaphor for his large mind, full of separate compartments, but with few comforts and no human voice to cheer, or hear, or console him. The samovar has always grown cold at Ivan's.

Father Ferapont's cell is correspondingly wild and hallucinatory, filled with flickering lights and the darkened images of saints, on the wild edge of a dark forest. Ivan takes refuge in tavern, but not even a private room: he is a man of the commons, always taken in the crossroads. His private space is not revealed until very late in the book; it happens to be a large-ish space, very private, with a gate and a deaf servant, full of rooms that he hardly uses. This is a metaphor for his large mind, full of separate compartments, but with few comforts and no human voice to cheer, or hear, or console him. The samovar has always grown cold at Ivan's.For Dmitri, there is an apartment where the landlords adore him, but more importantly his "look-out," a tumble-down gazebo: Dmitri is Pan. The gazebo is located in a paradise of a garden, however: there is a verdant meadow and a "thicket of lindens and old currant, elder, snow ball, and lilac bushes." Dmitri's gazebo is "blackened and lopsided, with lattice sides . . . everything was decayed, all the planks were loose, the wood smelled of dampness" (103-104). But, the roof "under which it was still possible to find shelter from the rain" and the little green benches, "on which it was still possible to sit" provide temporary shelter for a man destined for stone walls and no windows.

The women have their habitats, as well. Katerina Ivanovna's spacious digs are "filled with elegant and abundant furniture, not at all in the provincial manner." Here there is a silk mantilla, cups of chocolate, flowers in vases, and a "crystal dish with purple raisins, another with candies." There is "even an aquarium," a suitable metaphor for this hot-house lady's airless imprisonment by convention (144-145). Later in the book, however, this space seems to contract and is arduously up some narrow, dark stairs: her life prospects, along with her digs, have darkened and contracted. Grushenka's keeper has a house that is huge, dreary, "killingly depressing ," and although there are many large chandeliers, they are all wrapped in dust covers, so there is no chance of light (369).

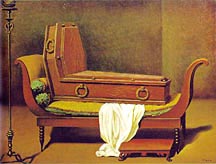

Grushenka's own home, a rented three-room wooden shack, is filled with discarded, oversized, and uncomfortable old mahogany furniture from the '20s (346). Alyosha finds her reclining on a torn leather sofa, with down pillows from her bed under her head for comfort. She cannot afford the candles, so lies waiting in the dark for "a golden message," but for Alyosha and Rakitin, she orders candles! champagne! (349). She spends her money on wardrobe, that is all. Of the Khokhlakov's interior, we know nothing, except that it is a fine house, and, near the vestibule, there is a sliding door, and later, a door that is shut painfully on Liza's finger.

Grushenka's own home, a rented three-room wooden shack, is filled with discarded, oversized, and uncomfortable old mahogany furniture from the '20s (346). Alyosha finds her reclining on a torn leather sofa, with down pillows from her bed under her head for comfort. She cannot afford the candles, so lies waiting in the dark for "a golden message," but for Alyosha and Rakitin, she orders candles! champagne! (349). She spends her money on wardrobe, that is all. Of the Khokhlakov's interior, we know nothing, except that it is a fine house, and, near the vestibule, there is a sliding door, and later, a door that is shut painfully on Liza's finger.Last but not least, Smerdykov migrates from his painful little room in Grigory and Marfa's house, big enough only for his cot, the scene of thrashing and suffering, to the "best room" in his fiance's home, which gradually fills up with furniture so that on Ivan's last visit, there is hardly room to move or sit. Grushenka's own torn leather sofa and now slightly soiled white pillows turn up there, but by this time, the mahogany is "imitation" (621). One wonders, how is this so? What communication has Grushenka with Smerdyakov that her sofa is now there?

Photo credits: "1) Traditional Russian Interior, " Courtesy Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey. 2) Rene Magritte, "Perspective: Madame Recamier by David, " 1956, from a West Valley College site on "Natural Surrealism." The original painting Magritte sent up is by David, from 1800, so this divan is about the right date for Grushenka's provincial imitation "from the twenties," so far from Paris, the fashion capital. Dostoevsky had a keen eye for details of style, and in particular had a keen sense ofthe ridiculousness of Russians slavishly copying Europeans, for example, Smerdyakov's studying French, like a nobleman, in his tawdry room.